The conversation around national identity has always been complex, often inviting a certain volatility. Possessing a pride in one’s nation is hardly an anomaly, yet the UK boasts an intriguing irony. Despite a welcoming message of multiculturalism, there is an inescapable sense of nationalism that breeds mistrust, and ultimately, division. By shining a spotlight on our 11th century past, we can begin to examine the origins of British identity. Is this identity actually constructed on a foundation of multicultural migration?

A United Kingdom?

National identity in the UK today has taken on a complexity not often seen in other countries. If you are from Greece, you are Greek. If you are from Portugal, you are Portuguese, and so on. However, when referring to the United Kingdom, some would identify as British, whereas others would identify as English, Scottish, Welsh or Northern Irish. Depending on the sport, we either compete as one nation or individual countries, while devolved parliaments exist in Wales, Northern Ireland and Scotland. As we live through the Brexit era, murmurs of independence from Scotland and Wales threaten the existence of our united kingdom. All in all it’s really rather confusing, isn’t it?

With all these factors at play, it’s not difficult to see why division exists as a result of identity dynamics in Britain. It may go some way to explaining the xenophobic rhetoric, often masked as ‘humour’, that flows in the undercurrent of society. From seemingly playful jokes about the French or Germans, to the openly hostile view of immigrants, there is an uncertainty towards those not from the British isles. The history of the United Kingdom is forever intertwined with immigration, conquest, war and, of course, colonialism, thus creating a fragile identity. To acknowledge our history is to expose the hypocrisy of British identity. By turning back the clocks to the turbulent times of the 10th and 11th centuries, we can begin to deconstruct who we are.

Despite the best efforts of several kings, Britain during the 11th century was anything but united. It was King Æthelstan (924 – 939), by forcing the submission of the Welsh and Scottish kings, then defeating a united resistance of Vikings & Scots in the Battle of Brunanburh in 937, who came closest to achieving the Anglo-Saxon vision of a single united kingdom. Despite his title of ‘Rex totius Britanniae‘ (King of the whole of Britain), Æthelstan never truly held dominion over the lands of Britain. Following his death in 939, the English kingdom fractured after further Viking incursions, thus ending the dream. As such, using the term British is not necessarily applicable; this is the history of the English, Scottish, Welsh and Irish kingdoms.

The Anglo-Saxon Kingdom

Alfred the Great: An Icon of the English?

Heading into the 11th century, England was a single, wealthy kingdom, united under the single banner of the Anglo-Saxon royal house. This was not always the case; England had once been split into different kingdoms, all vying for supremacy. The dream of a united England is often attested to King Alfred, remembered in history as the definition of the ultimate underdog story. Driven to a small Somerset marshland by the Great Heathen Army, Alfred gathered an army and drove the Vikings out of his Wessex homeland at the Battle of Edington in 878. The eventual peace deal even saw him convert the Viking leader Guthrum to Christianity in the process. Alfred the Great, as he is now known, began the House of Wessex – the first unbroken line of kings that would eventually rule the whole of England.

His achievements are remembered and celebrated to this day. For many, King Alfred is an icon of the English identity, used to further the cause of English nationalism. By using the image of Alfred as the ultimate in ‘English-ness’, it implies an acknowledgement of the origin of the Anglo-Saxons. At one time, following the fall of the Roman Empire, the Germanic tribes of the Angles and the Saxons were the invading foreign force, eventually settling in England. These tribes used a shared cultural identity to become what we know as the Anglo-Saxons. The establishment of the Anglo-Saxons required the displacement of or integration with the natives of the time – the Celtic Britons and the remnants of the Roman occupiers.

Confusingly, the British school system focuses on Roman Britain as the introduction of ‘civilisation’ to the country. The Anglo-Saxons form part of the ‘Dark Ages’, nothing more than an outdated phrase suggesting chaos and decline, used to further promote a common heritage with our Roman occupiers. In the case of both the Romans and the Anglo-Saxons, there is a fascinating observation to make: those we have adopted as the origins and icons of our national identity are none other than the one-time immigrants, invaders and settlers.

Viking England: An Anglo-Scandinavian World?

It is impossible to discuss the Anglo-Saxons without the Vikings. The two are intrinsically linked in the history of England. The first Viking raid came in 789 when Beaduheard, a royal reeve from Wessex was killed when three ships landed on the Isle of Portland. The attack on the Lindisfarne monastery in 793 signalled the beginning of increased incursions and the dawning of a new age in Anglo-Saxon history.

When discussing the Vikings, it is important to note that ‘Viking’ is not necessarily an accurate term to describe a people. Those that came to England hailed from Scandinavia, mainly Norway and Denmark. ‘Viking’ is most closely associated with ‘pirate’; in fact many argue that the correct use of the term would be ‘to go a-viking’. Within the 9th and 10th centuries, the Vikings were referred to by a variety of names: Danes, heathens, pagans, Norsemen and Northmen.

The invaders would soon become settlers, the descendants of which can still be found in the north of England today. When King Alfred finally drove the Great Heathen Army out of Wessex, he would sign an agreement with their leader, Guthrum. England was to be split; Wessex, Mercia and parts of Northumbria would remain Anglo-Saxon, while East Anglia and a large chunk of the Midlands would become the ‘Danelaw’.

The population in the north of England naturally became a hybrid of the Anglo-Saxon ‘natives’ and the new Scandinavian settlers. Many northern earls of the new English kingdom would be of Scandinavian descent, fully integrated into this new society. And if ever you wondered where the origin of the north-south divide in contemporary England lies, then search no more. The north was now a land of the ‘heathens’, where the ‘civilised’ Anglo-Saxons reigned in the south. Sound familiar?

Despite the best efforts of rulers such as Edward the Elder, Æthelflæd and Æthelstan to remove Viking rule from the north, the population had been altered forever. The elite were not, after all, the only Scandinavians who had integrated into England. However, Viking raids and invasions would continue throughout the Anglo-Saxon era. At their height, it drove King Æthelred (known to history as the Unready) to order the St Brice’s Day massacre – the systematic killing of Danes living throughout England. This must be one of the earliest examples of genocide, driven by the fear-mongering of the English elite.

As bad decisions go, there are few worse than this. In trying to prevent the Vikings destroying the English kingdom, it set in motion a chain of events that ended with Danish king Sweyn Forkbeard successfully invading the kingdom. Forkbeard may not have lasted long, but he paved the way for his son, Cnut the Great to become England’s coronated Viking king. His reign (and that of his sons) would last from 1016 – 1042, whereafter the English throne returned to the House of Wessex. As King of his North Sea Empire (England, Denmark, and Norway), Cnut blended the very best of the Anglo-Saxon and Scandinavian worlds.

When discussing the Vikings in England, once again we return to invaders-turn-settlers, integrating themselves into society. However, knowing violence as a result of an anti-foreigner rhetoric was prevalent in the 11th century shows that, in some ways, little has changed in the last 1,000 years.

The Norman Conquest

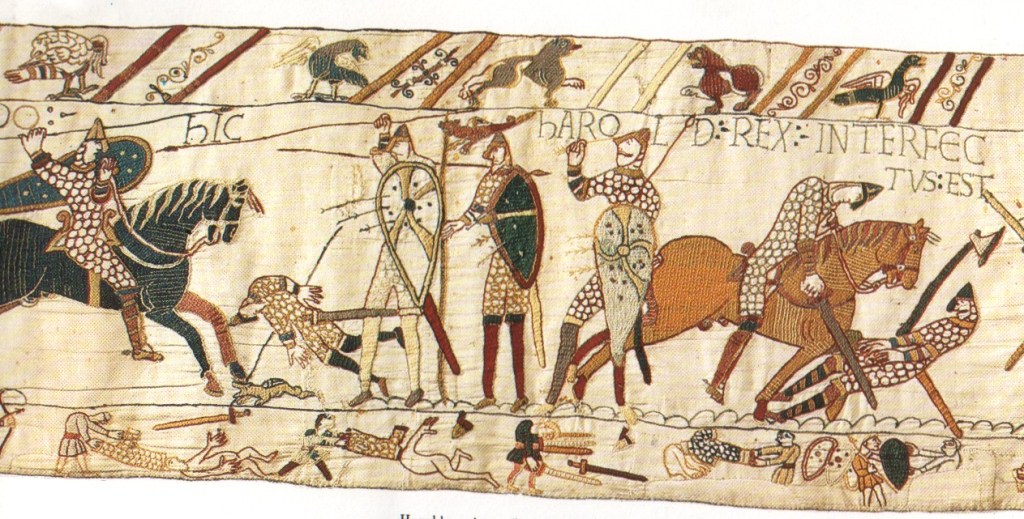

For anyone growing up in Britain today, they will be familiar with the story of 1066. The Battle of Hastings marked the end of Anglo-Saxon rule, signalling the start of a new Anglo-Norman kingdom, with William the Conqueror as the new king.

As the history books will tell you, it was King Harold Godwinson that lost his life that day. While many would argue he was the last Anglo-Saxon king of England, that may not necessarily be true. The rise of Harold Godwinson goes back to the time of King Cnut; his father, Godwin, served under the king. Godwin was rewarded for his service by not only the Earldom of Wessex, but with marriage to Gytha Thorkelsdóttir. Gytha was the brother of Earl Ulf, who was married to Cnut’s sister. Their marriage kickstarted the rise of the Godwin family as the most powerful in England. Following the death of the childless Edward the Confessor, Harold Godwinson was crowned as the new king. To describe Harold Godwinson as Anglo-Saxon would, therefore, be inaccurate. In reality, King Harold Godwinson was an Anglo-Danish king.

As a vassal state of France, Normandy began as a gift from King Charles the Simple to end Viking incursions into the Frankish kingdom. Hrólfr Ragnvaldsson (better known as Rollo) became the first leader of Normandy. The name Normandy comes from ‘Northmen’, the term used to describe the Viking invaders. The Normans integrated with the local Gallo-Roman population, creating a new state made up of the Norseman, Celts, Romans and Franks. Duke William of Normandy was Rollo’s great-great-great-grandson.

William’s decision to undertake the invasion of England was multi-faceted, and one which requires a whole study in itself, but what matters is that he did successfully overthrow the Anglo-Saxon kingdom. William’s army contained not only Normans, but forces from Brittany, Flanders and other regions of Europe. And how did he gather such an army? It’s simple really – promise of payment. William carved up English lands for those that helped him achieve his victory.

William the Conqueror may have become King of England, but in reality, during the first years of hie reign he only controlled the south. The limited but consistent resistance to his authority came from the north – the now ancestral home of the Anglo-Danish population. The new Norman dynasty would eventually bring the north under control; the brutal ‘Harrying of the North’ by King William in 1069-70 wiped out all that stood before him. The last remaining English aristocracy were removed and replaced by Norman nobility. Once again, therefore, we have an example of an invading force integrating itself into an already multi-cultural English society.

The Normans laid the foundations of modern Britain. William I is, in fact, the 22nd great grandfather of Queen Elizabeth II. And yet, discussions of the Battle of Hastings usually see a contemporary English allegiance with the Anglo-Saxon army of King Harold Godwinson. Due to more recent entanglements with the French (did someone say Napoleon?), it can be difficult for some to accept we may have more in common with the Normans than with our Anglo-Saxon ancestors. Despite everything, the Normans remain nothing more than an invading French force, taking on Harold and the ‘English’ underdogs.

A History of Invaders and Immigrants?

What, then, does it mean to be British? The United Kingdom of today is the combination of four distinct nations. As with any country, British history is a complex web of happenings, coming together to form the identity many hold today. To many, Queen Elizabeth II is the ultimate ‘British’ icon, despite the royal family being most definitely German. And now we know the Queen is also a direct descendent of the Norman conqueror of England, who himself was a descendent of a Viking invader. Consider then the propensity for jokes aimed at the Germans and the French, the punchline usually implying the superiority of the British. Somewhat ironic, wouldn’t you say?

Without this tumultuous period of change, adaption and conquest, the foundations for the British society we know today would never have been laid. Many aspects of the Anglo-Saxon period have been adopted and idolised by people who take pride in their identity. However, the legendary status of these past people has led to a worrying rise of cherry-picking the evidence in the formation of the ‘English’ identity. If we are to celebrate our past, we need to embrace it within the context in which it existed.

From the Anglo-Saxons, through the Vikings, all the way to the conquering Normans, the English past is characterised by immigration and invasion. The English kingdom of the 10th and 11th century was the envy of Europe, due in no small part to its economic prosperity. That prosperity, arguably, came from the adaptive qualities of the country. The Anglo-Saxons incorporated the settled Vikings into their kingdom, forming a powerful Anglo-Scandinavian society. When William the Conqueror took England for himself, he integrated Norman ideas into the kingdom while maintaining the successful English infrastructure.

From our place names, traditions, the English language (constructed of Anglo-Saxon English, Norman French and elements of the Norse languages of the Vikings), and even religion (Christianity was once an unwelcome immigrant on English shores after all), without the movement of these people into the country, through immigration, invasion, or otherwise, British society would not be what it is today. We are the United Kingdom thanks to the dream of King Alfred. We are Great Britain because we accepted multi-cultural migration and harnessed our diversity for success.

What does it mean to be British? To be British is to be proud of our past. To be British is to be proud our multi-cultural migratory origins. To be British is to welcome new ideas. We may be living in a different world to our Anglo-Saxon, Viking, and Norman ancestors, but without their cultural integration, there would be no us – there would be no United Kingdom. It is time we reject the rhetoric of division and embrace the power of diversity.

Who are we? We are Great Britain.