Who would have thought a film about archaeology could produce such an extraordinary rollercoaster of emotions? The Dig tells the true story of Sutton Hoo, interwoven with the heartbreaking personal stories of those responsible for its discovery. Having devoted my university education to archaeology in the public realm, The Dig symbolises more to me than just another enjoyable way to spend an evening. And for a world in the cruel grip of a pandemic, this film bestows a vital lifeline to the heritage industry.

When asked to name well known heritage sites within the UK, it comes as no surprise when people offer up the site that illuminated the Dark Ages – the Anglo-Saxon burials at Sutton Hoo.

First excavated in 1938, Sutton Hoo contained an undisturbed ship burial along with an abundance of Anglo-Saxon artefacts dating back to the 6th century. The discovery of the site was paramount in establishing an understanding of the early Anglo-Saxon period. It is believed the famous burial belonged to King Rædwald, known to history as one of the first Christian kings of East Anglia and one of the earliest to hold the title of bretwalda (rulers who had dominion over many English kingdoms).

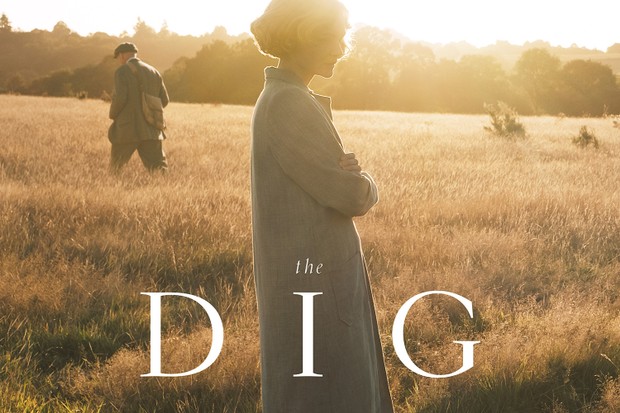

Archaeology is by definition the story of people, and the narrative cannot be complete without the stories of those who discovered the past; there would be no Sutton Hoo without Edith Pretty and Basil Brown. Edith Pretty was a recently widowed landowner who hired a self-taught excavator by the name of Basil Brown to investigate burial mounds on her property. This story was immortalised in the 2007 novel The Dig by John Preston, described as “a brilliantly realised account of the most famous archaeological dig in Britain in modern times“. In 2021, a film adaptation was released starring Carey Mulligan and Ralph Fiennes.

There’s no denying archaeology lacks a certain glamour, and yet The Dig expertly weaves academic intricacy into a captivating emotional elegance. First and foremost, from the systematic removal of different layers, the importance of health and safety, to the difficulty of removing important artefacts from the ground, the film meticulously details the excavation process. Surprisingly enough, The Dig accurately portrays the theoretical approach of archaeology during the 1930s; the culture-historical model focused on building a narrative through objects. It wouldn’t be until the 1960s when more scientific analysis would be introduced.

On the topic of excavation, The Dig shines a light on the single most important aspect of archaeology – community. Archaeology is people, and humanity thrived through community. And no excavation can be credited to a single person. Despite the poisonous politics, evident in the film through the fight for Basil Brown’s official recognition in reporting the find, archaeology is built relationships. The power of community illuminates the true power of archaeology.

Outside the dig itself, the film highlights some of the wider issues of archaeology, including that of human remains and the ethics of their excavation. Edith Pretty talks of “digging down to meet the dead“, affirming the close relationship between life and death, especially poignant given the impending start of World War Two. Basil Brown’s accident too offers a chilling reminder of the shared space for the living and dead afforded by the study of archaeology.

Even archaeology cannot escape the potency of politics. When the British Museum gets involved in the Sutton Hoo excavation, elitism rears its head as Brown’s work and abilities are completely disregarded, for no reason other than status. Even the local Ipswich Museum implores Brown to abandon the Sutton Hoo project in favour of a Roman villa. This traditional favouritism towards Roman remains is as powerful today as it was then; the ‘civilisation’ of the Romans over the ‘savagery’ of the Dark Ages has always been the favoured national narrative of British governments.

With national interest comes the lifeline of the heritage industry – funding. Basil Brown’s character however represents the true spirit of archaeology; a lifelong pursuit of passion, with no real ambitions other than an intrigue to understand the past. There is something so unapologetically grounded, charming, and heart-warmingly simple about Basil Brown’s approach to his work:

I do it because I’m good at it

Basil Brown, The Dig

And yet, to describe The Dig as merely a film about an excavation would be doing a considerable disservice to what is simply a multifaceted masterpiece of emotion. Set in the stunning East Anglian landscape, and despite the threat of war looming in every scene, the simplicity of country life inspires a feeling of childlike freedom and discovery. Even as the credits roll, the scene is nothing more than two people shovelling dirt. Any layers of drama and exaggeration are swept away, replaced by something pure, something refreshing, something real.

The lack of embellishment in the production creates a simple, smooth yet sincere backdrop to the central narrative, reflected exquisitely in the transition between scenes. As the previous scene melts away, character speech lingers, generating something of a spiritual echo, offering these words for deeper consideration. For like the archaeology itself, there is always something more beneah the surface.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_image/image/68674907/Dig_Unit_02187_R_CC_rgb.0.jpg)

Its the poignancy of the personal stories that give The Dig such strength. The character of Edith Pretty is seen questioning her own mortality as the chambers of the dead are revealed while her own health begins to fail. As her son tries to comfort his mum, Basil Brown’s words reminds him of the inevitability of our existence, all while encouraging him to make the most of the time we have:

We all fail every day, no matter how hard we try

Basil Brown, The Dig

This culminates in a heartbreaking scene where the young Robert takes his mum to the ship burial and tells her the story of a spaceman who finally reaches the stars. In one scene, the past and the present fuse together as the ship that held the bones of an ancient king will make one final journey so Edith Pretty can reach the heavens. And with that, we begin to understand the immortality of humanity. The relationship between past and present, and life and death, shines with utter clarity in a single, perfect moment. In this moment, previous complexity fades away to reveal nothing but raw emotion – such an inescapable feeling renders even the strongest of souls to tears.

From the first human handprint on a cave wall, we’re part of something continuous. So we don’t really die

Basil Brown, The Dig

True strength doesn’t always come from within, some films find success in their wider impact – The Dig has already justified its own existence through the positive reverberations on the heritage industry. It comes as no surprise the COVID-19 pandemic has decimated the archaeology and heritage sector, losing not just vital funding but public interest. Thus, the timing of The Dig’s release couldn’t be more ideal as Britain looks towards opening its doors once again. It has reignited a public fascination with the past; the exciting mystery of discovery will always shine bright in the human consciousness.

Since the film’s release, the British Museum has reported traffic to their Anglo-Saxon web pages has tripled, including a video of the famous helmet receiving 650,000 views since mid-January. On social media, #SuttonHoo was trending the week of release, while the film became the most watched film on Netflix in the UK.

I knew the film would be popular among fellow archaeologists and people interested in period dramas and that sort of thing, but it seems to have transcended those usual audiences and really touched a nerve with people

Sue Brunning – Curator of the Early Medieval collection at the British Museum and advisor on The Dig

The power of archaeology in popular culture is no more apparent than the Indiana Jones films, inspiring generations of children to pursue archaeology. The Dig has that same pull to inspire an interest in the past. Similar to the British Museum, the National Trust site at Sutton Hoo has seen a surge in online interest, now hoping this intrigue turns into visitor numbers once restrictions are lifted.

The British heritage industry survives on public interest. Increased exposure to a single site can create a rousing ripple effect, encouraging engagement with archaeological sites across the country, overseen by such guardians as English Heritage and the National Trust. As we emerge from the grip of COVID-19, cultural heritage represents an escape, a freedom, and a feeling of discovery we’ve been unable to appreciate for a long time.

From the sublime performances by Ralph Fiennes and Carey Mulligan, the inspirational presentation of the archaeological process, to the beautifully sentimental emotional narrative, The Dig is nothing short of a cinematic masterpiece. The film showcases archaeology as not only a passionate pursuit of the past, but a social narrative of those instrumental in its discovery; archaeology is the complete human story. And in a time of crisis for the industry, The Dig has harnessed the power of popular culture and thrust British heritage back into our collective consciousness in truly exceptional fashion. Put simply, it reminds us of the importance of archaeology – our past now exists in our present to inspire us towards our future.

The Dig is available to stream on Netflix.